Contents

1 Introduction

Via Evelyn Lamb on Twitter, I came across a neat proof of the double angle formula for the sine function that uses areas of triangle.

The double angle formula says that for any angle then:

The proof works out the area of a certain triangle in two different ways. Each way relates to one side of the identity, and as they are both computing the same thing they must be equal.

I like these kinds of proof as they show not only that something is true, but also give some connection to other concepts, in this case area, and linking ideas is a key goal in mathematics. I particularly like it as a demonstration of the method of proving identities by showing that two expressions are calculating the same quantity, whence must be equal.

But the best characteristic of a good proof is that it makes you want to go further. In this case, the "further" is to look for how to generalise this proof to one of the compound angle formula:

However, the journey I took from the given proof to a proof of the compound angle formula was not a straightforward one so this post is not just a demonstration of that proof but also how I got to it.

The point of doing that is that mostly proofs are presented without all the "construction lines". While this is often what is wanted, there's a place for showing how to get there.

2 Areas of Triangles

Let's start by looking at the proof of the double angle formula a little more closely.

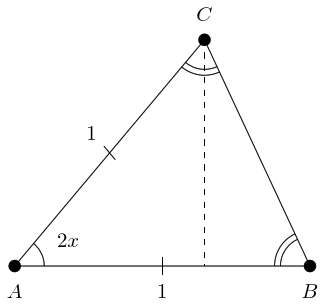

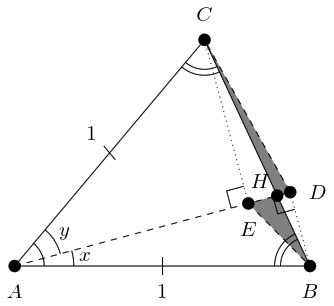

The proof referenced above can be thought of as two ways of calculating the area of an isosceles triangle. Let our triangle have apex angle and the two equal sides (which meet at the apex) length . If we consider one of the equal sides as the base, as in Figure 1, then the triangle has height so the area of the triangle is:

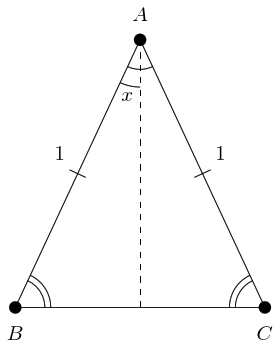

If we consider the third side as base, as in Figure 2, then we can think of it as two right-angled triangles with height and base , so the area of the triangle is:

Both are calculating the same thing, whence:

and the double angle formula quickly follows.

3 Generalisation

A neat proof is always nice, particularly when it brings in something unexpected. I prefer to think of the double angle formula as being about rotations1 but this proof brings in area. That's a nice bit of geometry to have, particularly as it links the double angle formula to the sine rule (which I do find easiest to think about in terms of area). So this has something going for it.

1And neat as this proof is, I still think of it as such.

But … I have a problem with it. A good proof should never just say why something is true. It should point to its being part of a bigger story2. The double angle formula is a special case of the compound angle formula which states that:

2For another example of this, see this about Pythagoras' Theorem.

So for me to classify this as a good proof of the double angle formula, it should point to a proof of the compound angle formula. Or maybe something else, such as the double angle formula for cosine, but given that it's about area then the compound angle formula for sine seems the most likely.

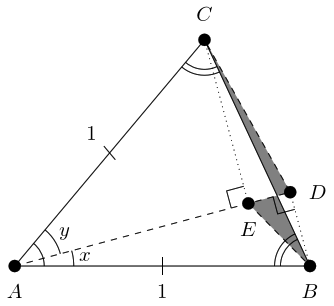

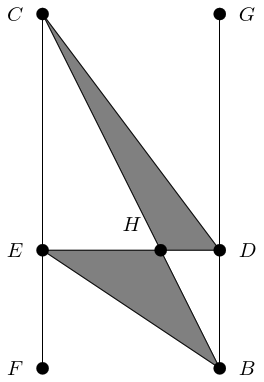

And no matter how I draw the triangles, I can't get them to work. The left-hand side, modulo a factor of , would seem to be the area of an isosceles triangle with apex angle (with one of the equal sides as the base). The right-hand side, again modulo a factor of , looks like it should be the areas of two other triangles. But the pictures don't nicely line up. Figure 3 is the best I can do.

In this construction, the dashed line out from splits the angle at so that the lower part is and the upper is . The dotted lines are the perpendiculars from this line through the other two vertices, and . These meet our line at and respectively, so that and are right-angled triangles. Thus is and is . We then join to and to to form non-right-angled triangles and .

The height of above is and so its area is . Similarly, has area . But the diagram does not explain why these two areas should add up to the area of the whole isosceles triangle because the two triangles and do not fit together to make the triangle . As the Figure 3 shows, one triangle pokes out and the other has a bit missing. The compound angle formula is tantamount to showing that the two shaded regions have equal area, something that does not seem obvious at all.

4 There and Back Again

At the current time, there is what seems to me to be a loud call to celebrate failure. So in the spirit of that, let me explain a big failure that I made in my approach to this generalisation.

Looking at Figure 3, I couldn't see why the shaded areas should be equal. So I ditched that diagram and went hunting for an alternative route. I ended up with what I felt was quite a neat construction using a rhombus and a few parallelograms. The eventual proof also used some circle geometry (the so-called "Butterfly Theorem") which I was particularly pleased with. However, while writing up the construction I felt it got a bit lengthy. It didn't have the simplicity of the original bisection.

I wrote it up with all the "construction lines" in (by which I mean the route by which I got to the proof). But when I got to the end, I had an urge to go back and tweak the final argument to simplify it. The more I did so, the more my proof began to look like the standard proof of the compound angle formula until at the end, like the animals at the end of Animal Farm, I found myself looking from my proof to the standard proof and not being able to tell the difference.

I think it important to note that it was only when I came to write it down that I realised all of the above. Writing down one's argument is crucial, as is looking back through it for places it can be simplified.

With a heavy heart, I erased my rhombus and parallelograms, and went back to stare at Figure 3 once more.

5 Similar Triangles

What my dead-end proof ended up doing was calculating a length in two ways. One way calculated it as , the other calculated it as the sum of two lengths one being and the other . I eventually decided that while one could dress it up in a variety of ways, fundamentally all proofs in which there are two lengths, one being and the other , will end up being essentially the same.

Figure 3 actually suffers from the same problem. The area of triangle is because the point is at height above the line .

What I really want is for the multiplication in to come from the calculation of an area. For that, I need two lengths, one and the other , at right-angles. Then I could get a rectangle or a right-angled triangle with area (modulo a factor of ).

There is a way to interpret Figure 3 to give me that. The idea is to turn the triangles around. For triangle , we consider the base. Then the "height" of above is given by the length of . So the area of that triangle is:

Similarly, we think of as having base and height , whence its area is:

This doesn't seem to have helped much because we still have the problem of the shaded regions. But making and the bases of these triangles had an effect on how I viewed them. One thing to keep in mind from the "half base times height" formula for the area of a triangle is that two triangles with the same base and same height will have the same area. This means that one can slide the apex of a triangle parallel to its base without affecting its area. By doing this, I ended up staring at something like Figure 4.

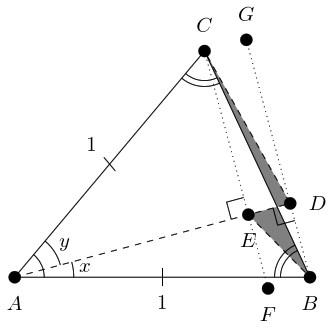

In Figure 4, is the result of sliding parallel to so that is perpendicular to . This makes triangle a right-angled triangle with having length and length . Similarly, is the result of sliding parallel to so that is perpendicular to .

Ultimately, considering the triangles and is not much use, which is why I haven't drawn them in Figure 4. But the diagram with and in them makes more obvious the fact that there are two parallel lines, and , and the shaded areas are somehow trapped in between. This focussed my attention on that specific part of the diagram and I decided to redraw it, but with a more suitable orientation.

Redrawing just this portion had the effect of focussing my attention on just the right spot. I should also confess at this stage to drawing this diagram in Geogebra and moving the points around. I had Geogebra keep track of the areas of the shaded regions so that I could see that they were equal no matter how far apart the other points were (subject to their staying in the same relationship).

Again, it took me longer to see the key than a simple write-up might indicate. I spent an inordinate amount of time focussing on the fact that the line was split into and . But, eventually, I realised what was going on.

As and are parallel, triangles and are similar (the fact that is perpendicular to has no relevance here). As they are similar, their sides are in proportion. In particular,

Multiplying up to clear the denominators, this shows that:

But as is perpendicular to and to , we have that is the height of triangle above and so is the area of triangle . Similarly, is the area of triangle .

Thus the similarity of and is equivalent to the fact that and have the same area3.

3This result stays true without being perpendicular to by virtue of the sine formula for the area of a triangle.

So the shaded regions are equal in area and the reason is … (drum roll) … Similar Triangles.

Again4.

4Honestly, I'm beginning to suspect that all of school geometry can be reduced to "because … similar triangles".

6 The Distilled Proof

Let's redraw Figure 3 with one more labelled point in Figure 6 and go through the steps one more time.

In Figure 6 then:

-

Triangle is isosceles with apex angle and equal sides length so has area .

-

Line splits the angle at into of size and of size .

-

Triangle has base of length and perpendicular height of length and so has area .

-

Triangle has base of length and perpendicular height of length and so has area .

-

The union of triangles and differs from triangle by the shaded regions. Specifically, triangle is added and is subtracted.

-

Triangles and are similar by virtue of and being parallel, hence and have the same area.

-

Hence the union of triangles and has the same area as triangle .

Conclusion:

(I still think of this as being fundamentally about rotations, though.)

7 Mapping the Route

I wrote this up to show the journey. Isaac Azimov is quoted as saying:

The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not "Eureka!" but "That's funny…"

The same goes for Maths. We have less opportunity than scientists to stare at the universe until something makes us say "That's funny" so we have to get used to going on fishing expeditions. That is, we have to play with ideas. So the phrase you should keep at the forefront of your mind in mathematics is: "What happens if …?".

In this case, it started from seeing a proof of a something that had a constraint and me saying "What happens if I remove that constraint?".

It also involved a fair amount of persistence, even for something as basic5 as the compound angle formula. Along the way, I ended up in several dead ends, even to the extent that I started writing up something I thought I had only for it to crumble around me.

5By which I mean that it is well understood in the mathematical community and the likelihood of someone coming up with a new twist on it being small; I do not mean that it is "basic maths".

In the end, the bit I'll take away from this is the part about similar triangles. I wasn't expecting that.

I'll still talk about rotation when explaining the compound angle formula, though.

A Cosine

I did wonder a little about whether there was a similar construction for the cosine formula – either double angle or compound angle. After a bit of thought, I came up with the following. It's not as elegant as the sine rule one, but I think that says more about the difference between the sine and cosine rules than about the specific constructions.

The construction is as follows. We start with the isosceles triangle as in Figure 2. Only this time, instead of calculating the area we calculate the length of the base, let's call it (as it is opposite angle ). Viewing the triangle as two right-angled triangles gives . Using the cosine rule says that satisfies the equation:

Putting these together yields:

which rearranges to:

and this is one of the forms of the double angle formula for cosine.

This definitely feels less elegant than that for sine. But let me rephrase the argument about sine. Again, let's calculate the length but instead of using the cosine rule we'll use the sine rule. This says that:

where is the side opposite . We have that and . Then as the triangle is isosceles, . From above, . Thus:

Using , this rearranges to:

namely, the double angle formula for sine.

This feels, to me, less elegant than the original area argument. It has the same reading on my elegance scale as the above argument for cosine. But it is equivalent to that original argument because the sine rule itself is a direct consequence of the fact that the area of a triangle can be calculated in a variety of different ways. So the original proof simply replaces the explicit use of the sine rule by an equivalent statement about areas and this gives it that more elegant feel as it phrases it in terms of more basic concepts. The cosine rule, on the other hand, is a generalisation of Pythagoras' Theorem and so it is less straightforward to express in terms of basic concepts. Thus an elegant rephrasing eludes me and we're left with the proof that explicitly uses the cosine rule.

(Despite all this, I'm still going to use rotations when teaching.)