Contents

1 Introduction

I've been thinking a lot about Pythagoras' theorem of late, beginning with finding my favourite proof of it and leading on from there. Along the way I found another proof that I quite like and which ranks as my second favourite. It's quite closely related to the Intersecting Chords theorem.

2 Proving Pythagoras

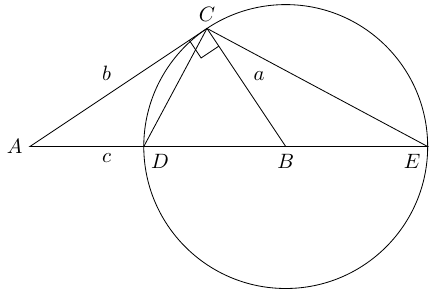

Consider the Figure 1, in which is a right-angled triangle with hypotenuse . The lengths are , , . The circle has centre and radius . The point is on the continuation of to the other side of the circle, making a diameter of the circle. Thus and .

As is a diameter, is a right-angle. We therefore have that:

Hence . Since is isosceles, .

The triangles and are therefore similar (with the vertices corresponding as just listed). Hence:

which, upon substituting in, yields

otherwise known as Pythagoras' theorem.

If we have already internalised the Intersecting Chords theorem then this follows much quicker since the tangent variant of that says that , but I prefer the above since it is more elementary (and see Section 5 for a small niggle about using the Intersecting Chords theorem here).

If you've read the account of My Favourite Proof then you'll be able to see why I quite like this one: similar triangles are at the forefront.

3 Extending Pythagoras: Acute Angles

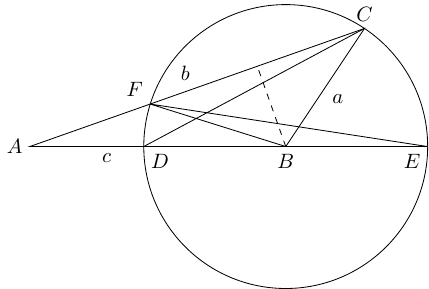

Also if you've read the account of My Favourite Proof, you'll know that I like my proofs of Pythagoras' theorem to extend to the cosine rule. So let's consider what happens if the angle at is not a right-angle. We'll start with it being less than a right-angle, as in Figure 2, in which we've assume that .

Exactly as before, the circle has centre and radius with a diameter. We also introduce the point as being the other place where the line intersects the circle.

The "Angles in the Same Segment" rule now says that and hence the triangles and are similar. Thus:

|

We know most of these lengths. The missing one is . To figure this out, we examine the triangle . This is isosceles, with base angle . Dropping the perpendicular, the dashed line in Figure 2, allows us to calculate the length of the base as . Hence and thus:

also known as the cosine rule.

Again, the Intersecting Chords theorem gives us Equation (1) immediately.

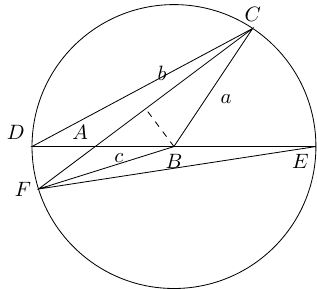

We assumed that was smaller than . If otherwise, the diagram looks like Figure 3.

As before, triangles and are similar leading to

Equally as before, . This time, and , so:

whence the cosine rule follows.

4 Extending Pythagoras: Obtuse Angles

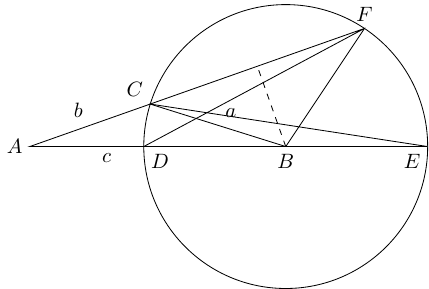

The case of an obtuse angle is actually very similar to that of an acute angle. The diagram is exactly the same as Figure 2 except that and are swapped, as in Figure 4 (there's no equivalent of Figure 3). This means that some lengths in the diagram have different interpretations in terms of , , and .

As and have swapped, the ratio is now:

The length is the same as before, except that the angle has changed so that . Thus .

If we define the cosine of an obtuse angle by then we can write .

Substituting in, we get:

whence the cosine rule again for obtuse angles.

5 But Only Second Favourite

Much as I like this proof, and its connection to the Intersecting Chords theorem, it stays in second place and doesn't replace my favourite. The reason for that is a small niggling worry about hidden assumptions. It's most obvious in the extension to the cosine rule: in each diagram, there's a crucial step where we have a line that intersects with a circle and we claim that there is an identifiable second intersection point.

This may seem blindingly obvious but it actually isn't. It is possible to set up a situation where this doesn't happen (it's easiest to set it up so that there are multiple intersection points). To do so, it turns out that we have to mess around with what we mean by "circle" which might feel a bit off, but until we've settled Pythagoras' theorem then we don't actually know what a circle looks like and it could, as far as we know, look quite different.

In other words, Pythagoras' theorem tells us what a circle looks like so until we've proven Pythagoras' theorem then we have to be very, very careful about what we assume about circles.

I think it's okay because the very first thing we do in this article, in Section 2, is prove Pythagoras' theorem. Once we know that, we can deduce some crucial facts about circles that we use in Sections 3 and 4. And I don't think that Section 2 uses anything special about circles (this is in part why I prefer the direct method rather than using the Intersecting Chords theorem). The only "fact" that we use is that in Figure 1 is a right-angle. This is proved using isosceles triangles which depends on the fact that every point on the circumference of the circle is a fixed distance from its centre – and that is the fundamental definition of "circle". In particular, we don't use the fact that the angle between a radius and tangent is a right-angle. The angle is a right-angle, but that's part of the initial information. At no point do we need to know that the line segment is tangential to the circle (which we would need if using the Intersecting Chord theorem).

Once we have Pythagoras, we can show that if a line crosses a circle at a point such that it makes a angle with the radius to that point which is not a right-angle then it must cross the circle at another point (on the side where the angle is acute). Once we know that, then I think that Sections 3 and 4 follow without any additional hidden assumptions.

So nice as it is, it stays below my favourite proof of Pythagoras' theorem.

As this last section is about niggles, I'll leave with two statements. Both are "obvious facts" about circles and lines, but both are ones that I find hard to give elementary explanations for. These are often either assumed or stated early in geometry and possibly never questioned. To be clear, I know how to prove them in the context of modern geometry, but I don't think I have a good "this is why it's obviously true" that I could give to a new geometer. Anyway, the statements are:

-

(From above) if a line intersects a circle such that it makes an angle with the corresponding radius that is not a right-angle then it intersects the circle at exactly one other point.

-

(And its converse) if a line intersects a circle at a single point then that line makes a right-angle with the corresponding radius.

I'd be interested in learning of the explanations people give for these two.